GLOBALISATION

Today, we're looking at medieval Europe from a global perspective in our tutorials. The fourteenth century is an intriguing period in this respect - often overlooked in our excitement at fifteenth century European exploration and discovery - fourteenth century Europe was characterised by increased contact with the Mongols (an alliance against the Turks was even mooted), trade routes stretching from Genoa to China, missionary activity across Asia and into China, pilgrimages and even some cultural exchange.

Fifteenth-century depiction of Alexander the Great flying (having explored the entire known world): Roman d'Alexandre, Ms.651/1486,Musee Conde, Chantilly, France

Global history is a relatively new phenomenon in the field of medieval studies. It does two things: it draws our attention beyond Europe and helps us to readdress our very Eurocentric vision; and it provides methodologies for thinking about interconnections and exchange across boundaries. The first of these is very difficult to achieve, primarily because of the enormous range of languages this requires of researchers. Which doesn't mean to say that scholars are not going to try to take up the challenge: the recent book by Giorgio Riello on cotton re-centres the story on India in the Middle Ages.

There is a third reason why it is important to look at medieval history from a global perspective. That is that such a perspective sheds new light on the history of ideas and identities: how Europeans understood themselves, and how they conceptualised difference. Europeans in the Middle Ages seem to have been quite aware that the world they inhabited was, in many sense, expanding. And travel literature was immensely popular. Increasingly, they were able to draw on empirical observation to see that their everyday surroundings were not universal, that this was a world characterised by diversity and different ways of doing things.

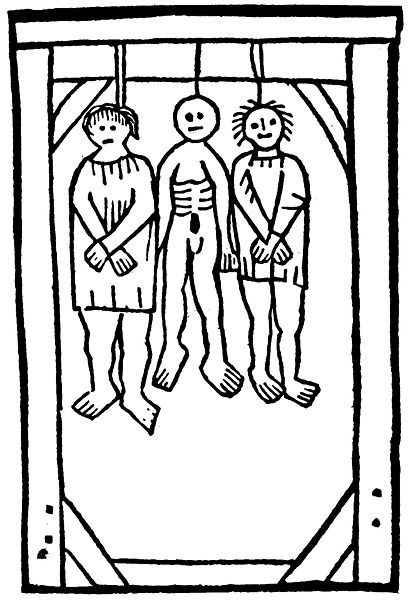

And yet, the ways in which they described those new discoveries and observations could only be done within familiar frameworks. Riello reproduces a particularly striking illustration from the Travels of Sir John Mandeville, an exceptionally popular fourteenth-century text, which describes, in highly imaginative terms, the wonders and marvels and monsters of the wider world.

This is, apparently, a cotton plant. 'There grew there [India] a wonderful tree which bore tiny lambs on the endes of its branches. These branches were so pliable that they bent down to allow the lambs to feed when they are hungrie.' What I love/ find troubling about this description and the image is the way in which Mandeville imaginatively recreates what is to him and his readers an utterly strange plant in terms of the familiar. In England, cloth production was of wool. So what better way to try to convey to his armchair readers this exotic Indian form of cloth production that in terms of a kind of weirdly contorted animal husbandry which allowed Europeans to understand the different in familiar frameworks, as well as creating an intoxicating sense of the monstrous and deviant?

I wonder how often, nowadays, media accounts of happenings in distant lands actually squash a more complex reality into familiar frameworks. And how often we allow genuine attempts to understand cultural differences to become overlaid with Eurocentric concepts which make the different automatically appear deviant.

_-_Walters_W10613R_-_Full_Page.jpg/447px-William_de_Brailes_-_The_Israelites_Worship_the_Golden_Calf_and_Moses_Breaks_the_Tablets_(Exodus_32_-1-19)_-_Walters_W10613R_-_Full_Page.jpg)