'ONLY MADMEN ARE CERTAIN AND DECIDED'

(Michel de Montaigne, Essais, 1.26)

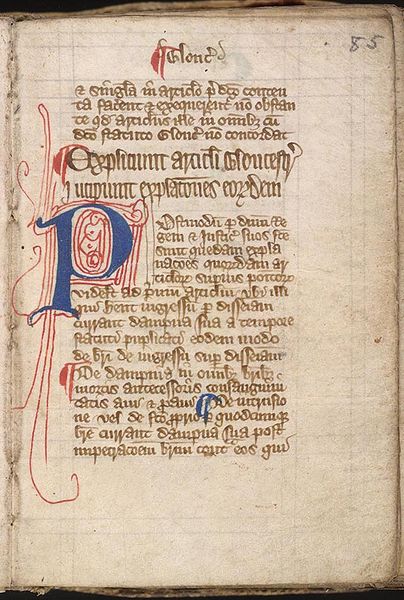

Anonymous portrait of Michel de Montaigne

Having reached the end of term, this seems like a good moment to stop and think about what I'm trying to achieve with this blog. If I could meet anyone from the past, I think I would choose Michel de Montaigne. His Essais are a companion through life. And what I admire so much about Montaigne is his exploration of the idea of doubt. Through what he writes, as well as the way he writes it, he challenges dogma and certainty, whilst retaining moral integrity - to be able to hold the two in tension should be, I think, one of the greatest goals of civilisation.

With Montaigne as my guide, then, what I'm trying to do with this blog is to challenge myself to doubt and to question. And it strikes me that this is really why I study history. The past does not hold any keys for the present, but it provides us with ways to challenge ourselves and to reveal disjunctions, discontinuities and hypocrisies in our ways of thinking and responding to current events. In other words, it enables us to throw our dogmatic responses into critical doubt.

Montaigne certainly didn't 'invent' doubt though. Medieval discussions of doubting Thomas, the figure who couldn't bring himself to accept Christ's resurrection and had to touch his wounds before he believed, are fascinating in this respect.

Christ and Doubting Thomas, between 1477 and 1482, from the Basilica of Santa Casa, Loreto

Thomas was referred to

disparagingly by early medieval theologians – as an unbeliever, he was an embarrassment - St. John

Chrysostom, for example, described Thomas as ‘grosser and more materialistic’

than the other apostles, and cited him as the epitome of the weakness of human

faith and the inadequacy of many Christians – Thomas’s faith was insufficient

to convince him of the miracle of the resurrection, and he would only believe

when presented with visual evidence.

In the later Middle Ages though, Thomas was reassessed. An increasingly positive conception of the

role of the senses in the spiritual life, particularly encouraged by the

materialistic preoccupations of a growing commercialism, re-validated the

figure of Thomas as one whose faith was based upon empirical evidence, and

whose concerns about the origins of

knowledge were shared by medieval people, particularly merchants,

struggling to get to grips with shifting environments.

Second, anxiety about the Docetist and Arian

heresies which negated the corporeal aspect of Christ’s humanity, meant

that Thomas’ emphasis on the physical body of Christ was particularly

welcomed by the established church and orthodox theology. Thomas became the model theologian.

But third, and most importantly, Thomas was

increasingly cited as a model for believers – his own personal journey

from unbelief to belief described as paradigmatic for the Christian

experience.

Commentators, notably Bede,

focused upon the etymology of Thomas’s name, claiming that it originally mean

‘double’ or ‘twin’, and explaining that this ‘doubleness’ lay in his twin

personality as the sceptic and the believer.

It was Gregory the Great and his increased focus on the Eucharist and

the body of Christ, who most enthusiastically established Thomas as a model to

whom Christians could look as they addressed their personal experience of

journeying spiritually from scepticism to faith, or from ignorance to understanding.

I find it really quite inspiring that doubt was given such a positive write-up in the Middle Ages, a period so often dismissed as an era of darkness, intolerance and dogmatism. The figure of Doubting Thomas was used to suggest that doubt and scepticism are common to us all, but not only that, they are epistemologically and spiritual useful - that is, they are attitudes which allow us to explore and critique and challenge in new and productive ways.

In the early fourteenth century, Dante wrote 'che non men che saper dubbiar m'aggrada' ('it pleases me no less to doubt than to know' - Inferno, XI, 93) - he is quoted by Montaigne, although Dante's point is slightly different as he is claiming that doubt and questions ultimately lead to greater precision. But the sense of critical doubt is very similar. Do not take anything for granted; challenge your preconceptions; examine incongruities and try to highlight discontinuities and hypocrisies. That is just what I am trying to do in this blog.

If you're interested in Doubting Thomas, see Alexander Murray, Doubting Thomas in Medieval Exegesis and Art (Rome, 2006).