SLAVERY 2

As

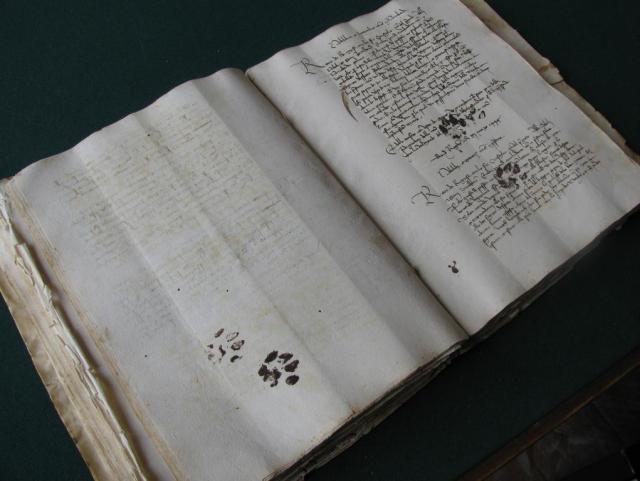

I said in a previous post, I shall be spending September in the archives in

Dubrovnik, looking for cases of late medieval slavery (and I hope to post

regularly on the blog during my time there).

|

| Dubrovnik: image wikicommons |

My interest in this arises out of a collaborative project on the subject

of ‘LEGALISM’. Anthropologists and

historians have been getting together at St John's to think about the implications of law as

the explicit use of generalising concepts as a way of thinking about human life

and social relations. We’re now beginning

to address the question of property and ownership and have heard wonderful

papers on ownership of water, of scientific ideas, and of labour. My contribution to the Legalism project at this stage will (I hope) be an examination of the legalistic implications, and legal culture surrounding and underpinning, late medieval slavery in Dubrovnik.

When

you begin to break down deep-rooted assumptions about property, its logic

begins to seem really pretty bizarre. If

the credibility of positive law usually rests on its supposed closeness to

natural law – to what seems logically, instinctively, morally right – property is

quite difficult to justify.

Aristotle

had a go, and came up with four main justifications (and I apologise for the

wild simplification): first, private property encourages productiveness and

incentivises; second, its rewards sustain a sense of fairness; third, it is

deep-rooted in man’s nature; and fourth, it provides an opportunity for

generosity and benevolent behaviour.

|

| Aristotle: image from wikicommons |

I’m

not convinced of the universality of these arguments: they are certainly

foundational in our culture, but that may just be another indication of their

contingency.

Whilst many of us accept quite unquestioningly the type of logic Aristotle comes up with for private property,

assuming that it refers to land, houses or goods, we do not view the ownership of

other human beings in such terms – indeed, we know that it is abhorrent, and

more than that, we feel that it is bizarre.

Aristotle addresses the issue of slavery in the same sorts of terms as we saw above. His first question relates precisely to the issue

of whether slavery is merely conventional, contingent, a matter of positive

law; or whether the positive law underpinning slavery maps onto natural law, to

what is instinctively, morally, naturally right.

And

yes, Aristotle claims that slavery is justified by natural law. Because, he tells us, some people are

naturally marked out for slavery; slavery is a critical element of the well-being

of the political community; whilst distinctions exist between man and beast, so

natural distinctions exist between slave and master.

There

are many more subtle distinctions in Aristotle’s approach, but you get the

gist. The point is, at this stage, that

if we feel his assumptions regarding slavery to be so problematic, we need to

re-interrogate his assumptions regarding property more generally – assumptions with

which we have all been implicitly brought up.

So,

I hope that my research trip will provide some useful insights into the

legalism of late medieval slavery, but more than this, will suggest ways of challenging

and understanding our assumptions about property more generally.

(nb. See Book I, Chapters iii to vii of the Politics and Book VII of the Nicomachean Ethics)